Hip-hinge exercises

Movement patterns and classification

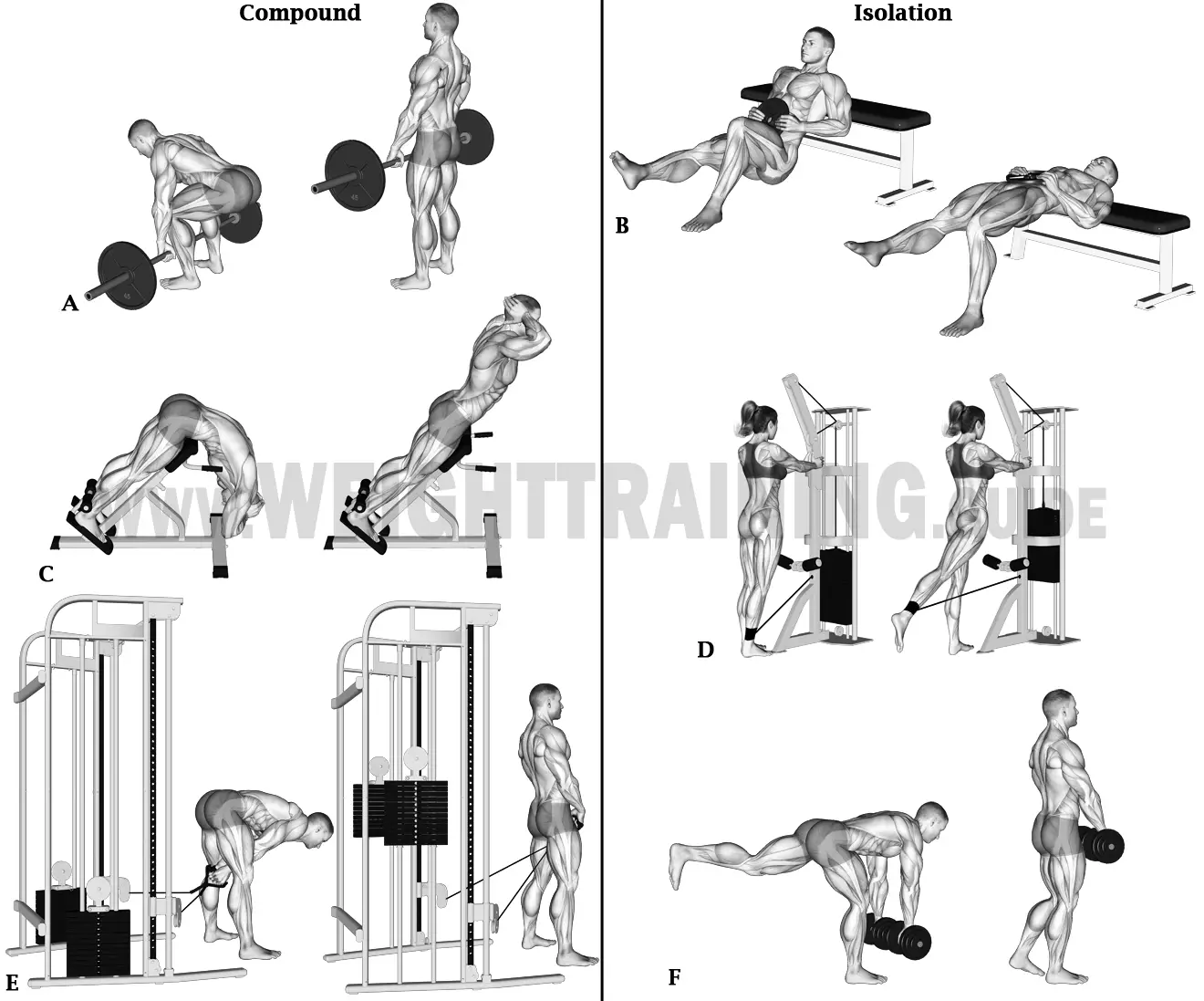

Hip-hinge exercises (for example, Figure 1) are primarily characterized by hip extension but may also incorporate either knee extension or waist extension. This is a large and diverse group of exercises, the most popular of which is the barbell deadlift, which basically involves squatting, grasping a barbell with both hands, raising your torso upright, standing up, and pulling the barbell up the front of your legs with straight arms, before lowering it back down to the floor (Figure 1, A).

If a hip-hinge exercise solely or primarily utilizes hip extension (for example, the weighted single-leg hip thrust and the standing cable hip extension; Figure 1, B and D, respectively), it is classified as an isolation exercise. If a hip-hinge exercise combines hip extension with either knee extension or waist extension (for example, the barbell deadlift and the 45-degree hyperextension; Figure 1, A and C, respectively), it is classified as a compound exercise.

Figure 1. Examples of compound and isolation hip-hinge exercises. A. barbell deadlift; B. weighted single-leg hip thrust; C. 45-degree hyperextension; D. standing cable hip extension; E. straight-leg cable pull-through; F. single stiff-leg straight-back dumbbell Romanian deadlift.

Muscle activation

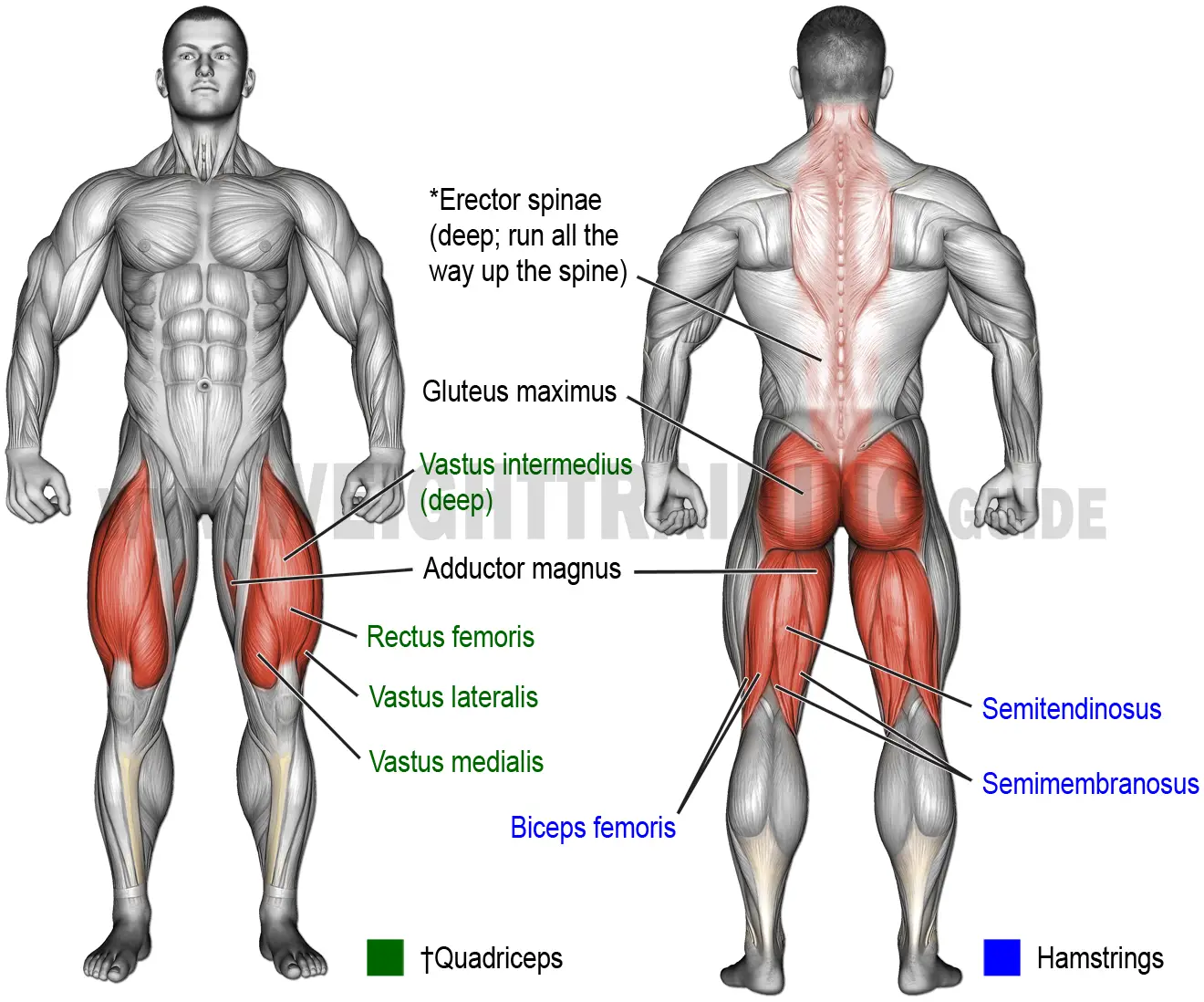

Muscle activation in hip-hinge exercises is a little complicated because the group of exercises is so diverse. However, generally speaking, hip-hinge exercises activate your gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and adductor magnus because these are the muscles involved in hip extension (Figure 2). Whether other muscles are activated depends on whether any other movement patterns are involved:

- If the exercise incorporates knee extension (for example, the weighted single-leg hip thrust; Figure 1, B), your quadriceps are activated

- If the exercise incorporates waist extension (for example, the 45-degree hyperextension; Figure 1, C), your erector spinae are activated

Figure 2. Main muscles activated by compound and isolation hip-hinge exercises. *If waist extension is involved, can act as either synergists or target. Can also be significantly activated as stabilizers if the exercise involves maintaining a neutral spine while lifting a heavy weight, such as with the barbell deadlift. †Synergists only if knee extension is involved, such as with the weighted single-leg hip thrust.

In isolation hip-hinge exercises, the target muscle group can be either your hamstrings or gluteus maximus depending on how extended you keep your knee as you extend your hip. If you keep your knee extended, your hamstrings will be the target muscle group, whereas if you keep your knee flexed, your gluteus maximus will be the target muscle. The reason is that the more extended you keep your knee while extending your hip, the more stretched your hamstrings will be, allowing them to make more of a contribution to the movement. In contrast, the more flexed you keep your knee while extending your hip, the less stretched your hamstrings will be, forcing your gluteus maximus to make more of a contribution to the movement.

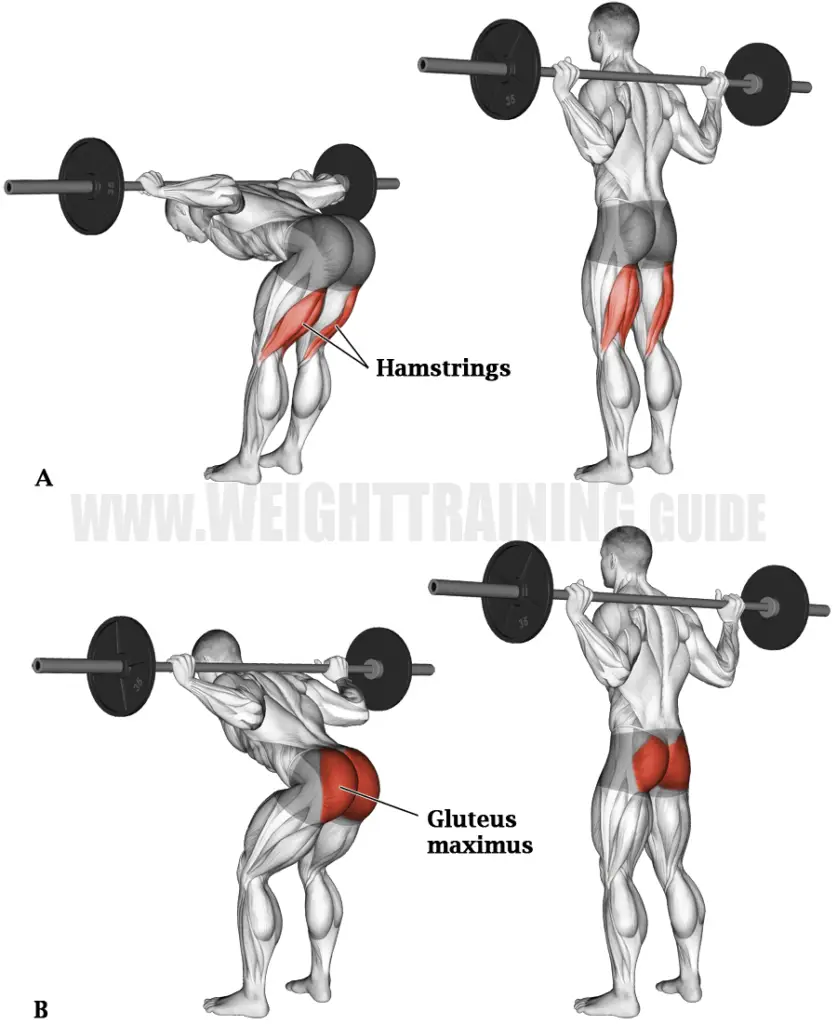

Two exercises that illustrate this trend well are the barbell good-morning, which is performed with extended knees, and the bent-knee barbell good-morning (Figure 3, A and B, respectively). Both exercises activate your hamstrings, gluteus maximus, and adductor magnus, but the barbell good-morning targets your hamstrings, whereas the bent-knee barbell good-morning targets your gluteus maximus.

Figure 3. The barbell good-morning (A) and the bent-knee barbell good-morning (B), with the target muscles indicated. Bending the knees results in the target muscle changing from being the hamstrings to being the gluteus maximus.

In compound hip-hinge exercises, the target muscle group can be either your hamstrings, gluteus maximus, or erector spinae, depending on how extended you keep your knee as you extend your hip and how much waist extension is involved. For example, with the straight-leg cable pull-through (Figure 1, E), the knees are kept extended and there is more hip extension than there is waist extension, so the hamstrings are the target muscle group. On the other hand, with the 45-degree hyperextension (Figure 1, C), although the knees are kept extended, there is more waist extension than there is hip extension, so the erector spinae are the target muscle group.

As to the barbell deadlift, the knees are flexed during hip extension, so the hamstrings can’t make as much of a contribution to the hip-extension movement as they could if the knees were extended. The adductor magnus and, in particular, the gluteus maximus make the greatest contributions to the movement, so the gluteus maximus is the target muscle. However, if you lift a heavy weight, it can be argued that your erector spinae may become the target muscle group even though there is no significant waist extension and your erector spinae are mainly acting as stabilizers. The reason is that the pressure placed on your erector spinae to stabilize your back/core may exceed the pressure placed on your gluteus maximus.

Note that, being a major full-body exercise, the heavy barbell deadlift can also significantly activate your calves (soleus and gastrocnemius), upper and middle trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and wrist flexors.