How muscles work

Motor units

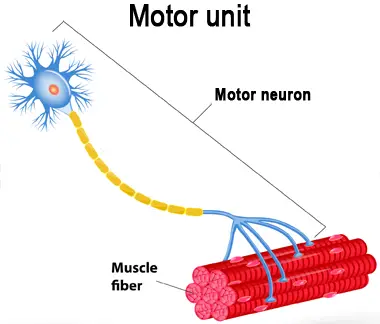

Your skeletal muscles are controlled by your somatic nervous system. Muscle contractions are activated by nerve cells called motor neurons (Figure 1). A single motor neuron may stimulate between one and several hundred muscle fibers. Some motor neurons activate Type I fibers, whereas others activate Type IIa or Type IIb fibers. A motor neuron and the fibers that it stimulates are collectively called a motor unit. If a motor neuron fires, it activates all of the muscle fibers in its motor unit.

Figure 1. A motor unit, consisting of a motor neuron and the muscle fibers that it activates.

How motor units are recruited for contraction

The contraction of a single muscle is often coordinated by groups of motor units. The number of motor units involved in the contraction depends on the amount of load. If the load is light, a relatively small number of Type I motor units will be recruited. As the load increases, more Type I motor units will be called into action, followed by Type IIa and Type IIb motor units, until all of the muscle’s motor units are utilized. This means that the only way to stimulate the entire muscle is to work with weights that are personally very heavy.

How muscles contract

As mentioned in Muscle structure, muscle fibers are composed of cylindrical strands called myofibrils, which are in turn composed of filaments of the proteins actin and myosin. The filaments, known as myofilaments, repeat in units called sarcomeres. The two ends of each sarcomere are marked by a Z disc.

Sarcomeres are the basic functional units of muscle fibers. If you understand how sarcomeres function, you will understand how muscles work.

Put simply, when an impulse from a motor neuron reaches the muscle fiber, it creates chemical changes that cause the actin filaments to slide along the myosin filaments, which shortens the length of the sarcomere and thus changes the length and shape of the muscle fiber (Figure 2). Once the stimulation stops, the actin and myosin filaments move apart, and the sarcomere (and thus the muscle fiber) returns to its resting length and shape.

More specifically, the thick myosin filaments possess protruding heads that can bind to the thin actin filaments. When an impulse hits the muscle fiber, the protruding heads of the myosin filaments bind to the actin filaments, after which the myosin filaments undergo a change in shape. The change in shape cocks the protruding heads of the myosin filaments, which pulls the actin filaments inwards. Since the actin filaments are anchored to the ends of the sarcomere (the Z discs), the sarcomere shortens in length. All of the sarcomeres in the muscle fiber shorten at the same time, producing the action that we call contraction.

Figure 2. Muscle fiber contraction. Muscle fibers contract at the level of the sarcomere when thin actin filaments slide over thick myosin filaments as a result of chemical changes initiated by an impulse from a motor neuron.