Introduction, joint articulations and the three planes of motion

Introduction to the Muscle Activation Guide

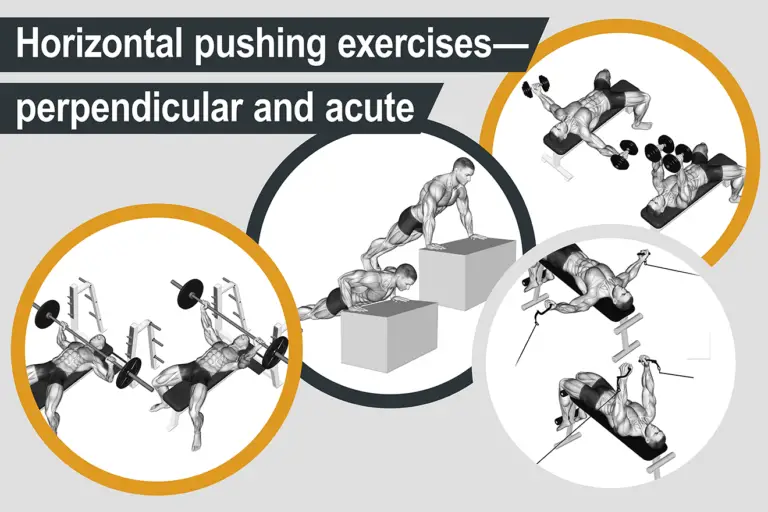

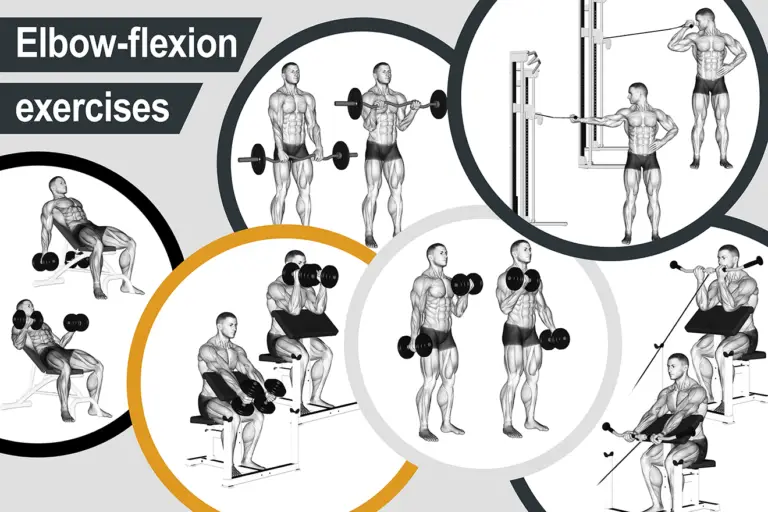

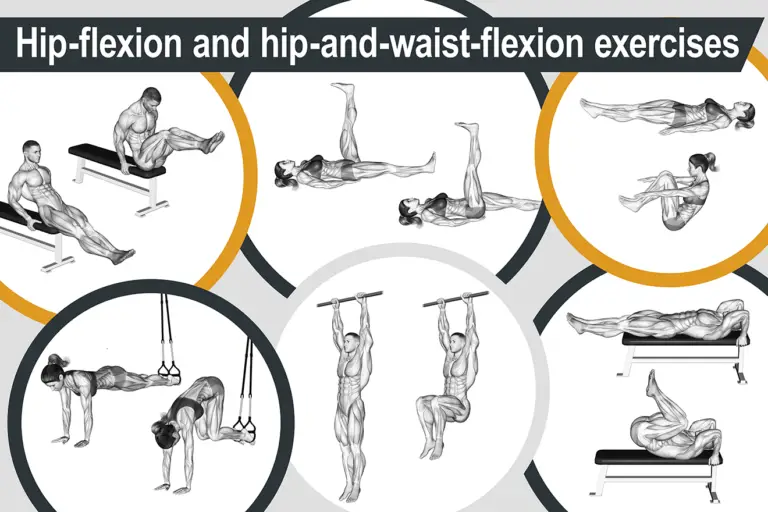

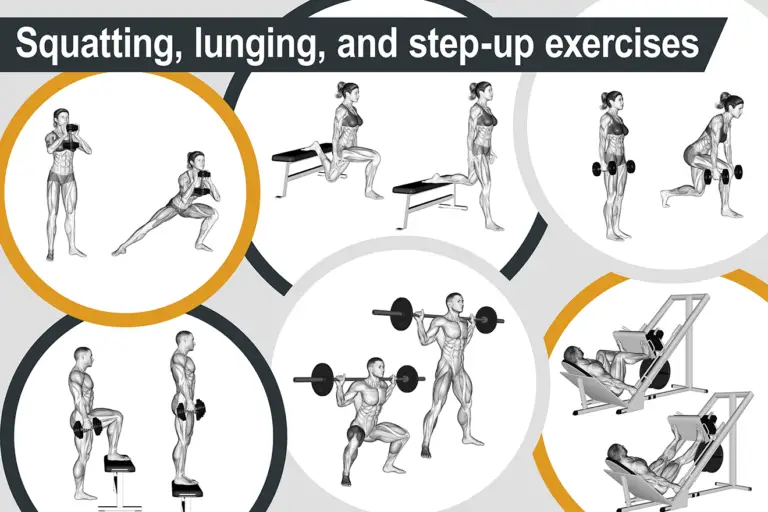

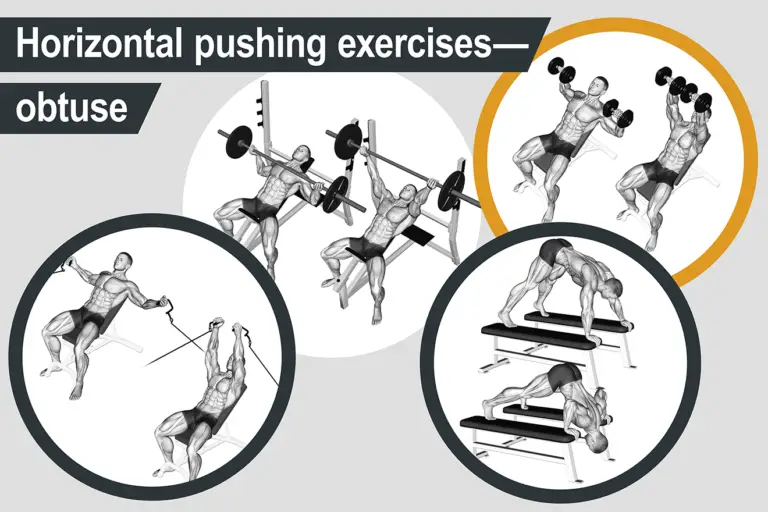

Exercises can be very similar. They often follow the same or a very similar movement pattern, such as a vertical pull or a horizontal push. Generally speaking, exercises that follow the same movement pattern activate the same muscles.

The Muscle Activation Guide provides a general overview of the main muscles that are activated by exercises that follow all major movement patterns. By ‘main muscles’, I mean the target muscle (the muscle that is most involved in the movement or put under the most pressure) and the synergistic muscles (the muscles that help the target muscle). Unless important, I shall not discuss stabilizer muscles, because they will overcomplicate matters.

I start the Muscle Activation Guide with an overview of joint articulations and the three planes of motion. You will need an understanding of these subjects to understand this guide.

Joint articulations and the three planes of motion

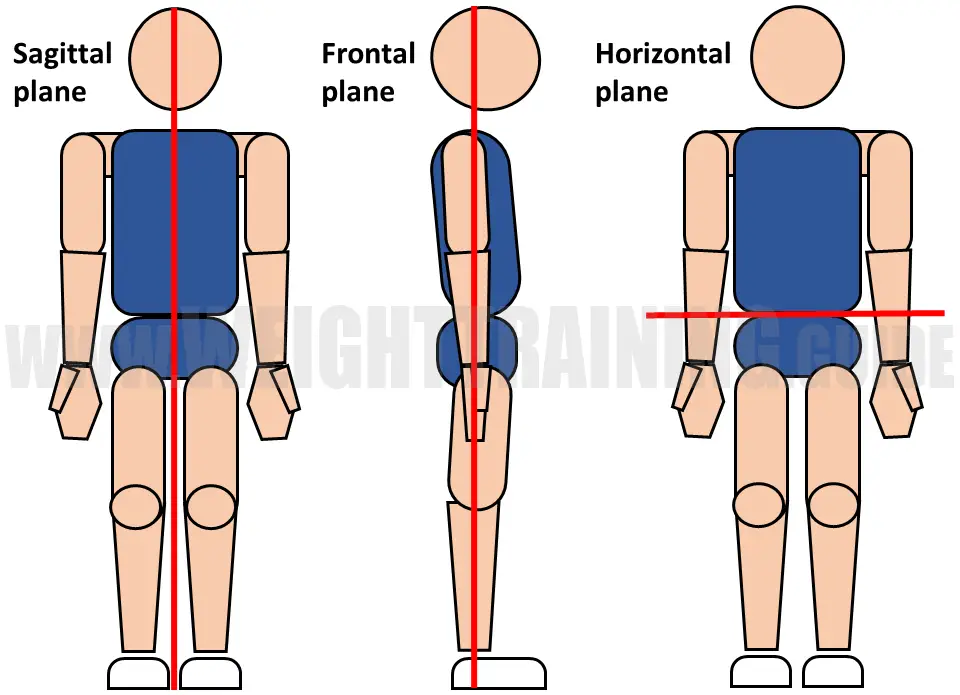

Your body can move in three planes: sagittal, frontal, and horizontal (Figure 1). The anatomical position, as illustrated in Figure 1, is the starting position of nearly all movements.

Figure 1. The anatomical position and the three planes of motion: sagittal, frontal, and horizontal.

Joint articulations in the sagittal plane

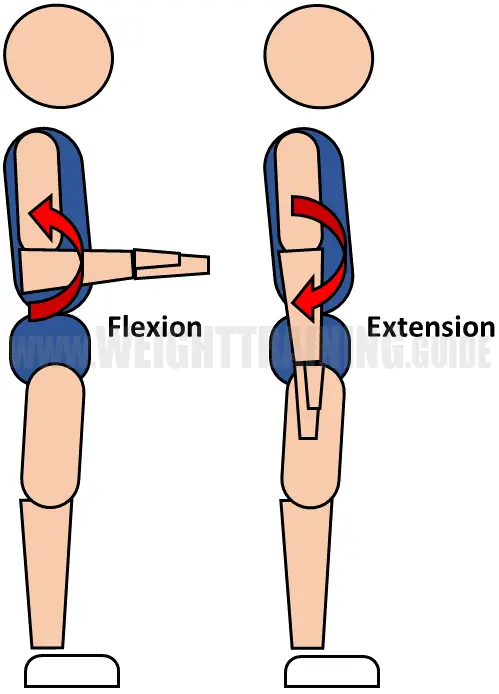

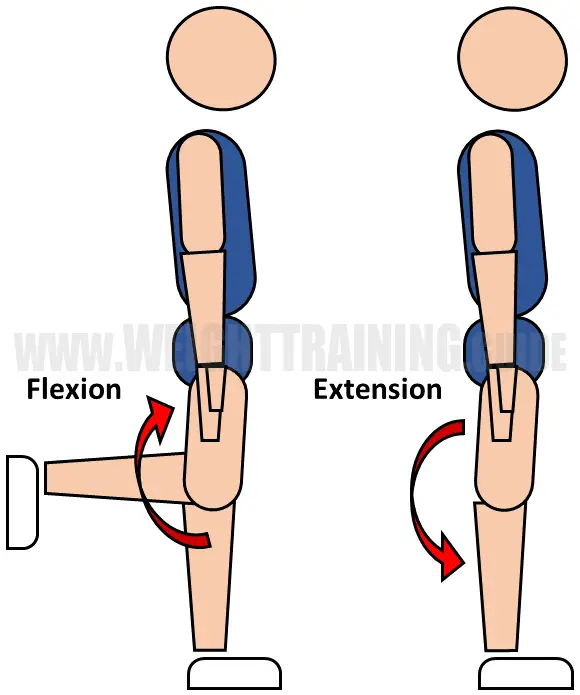

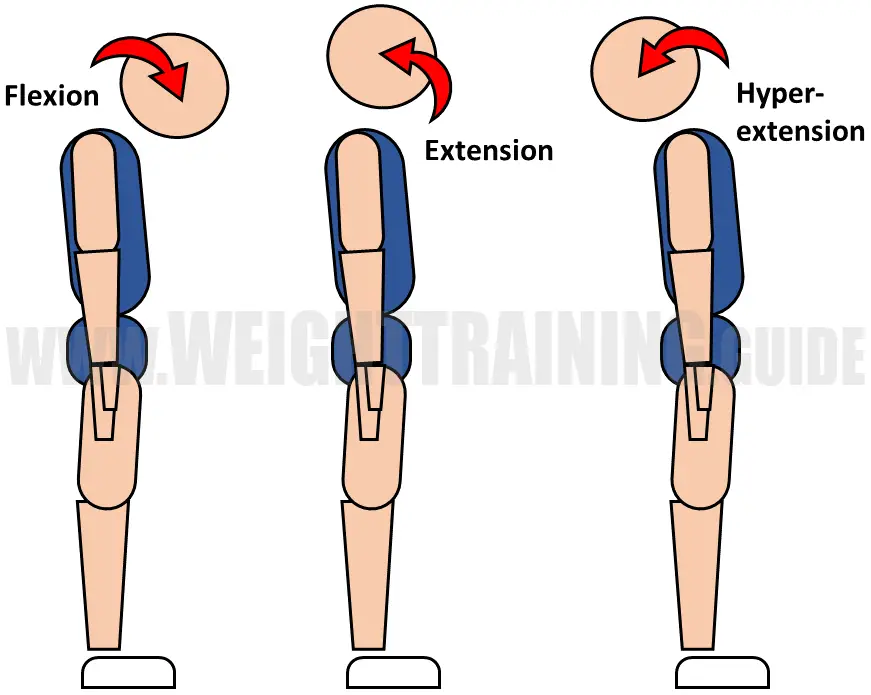

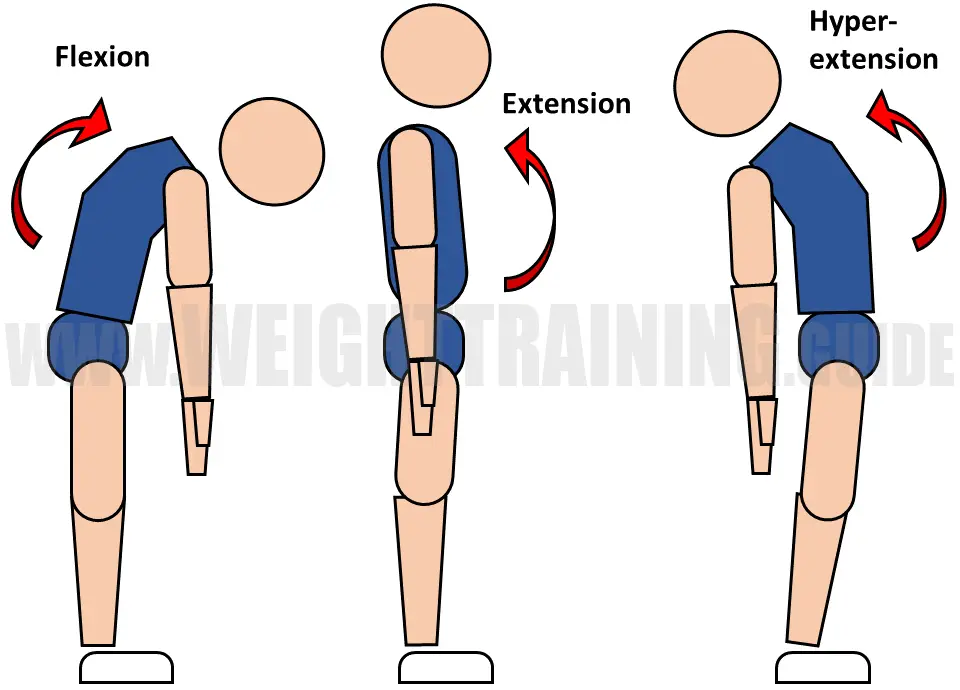

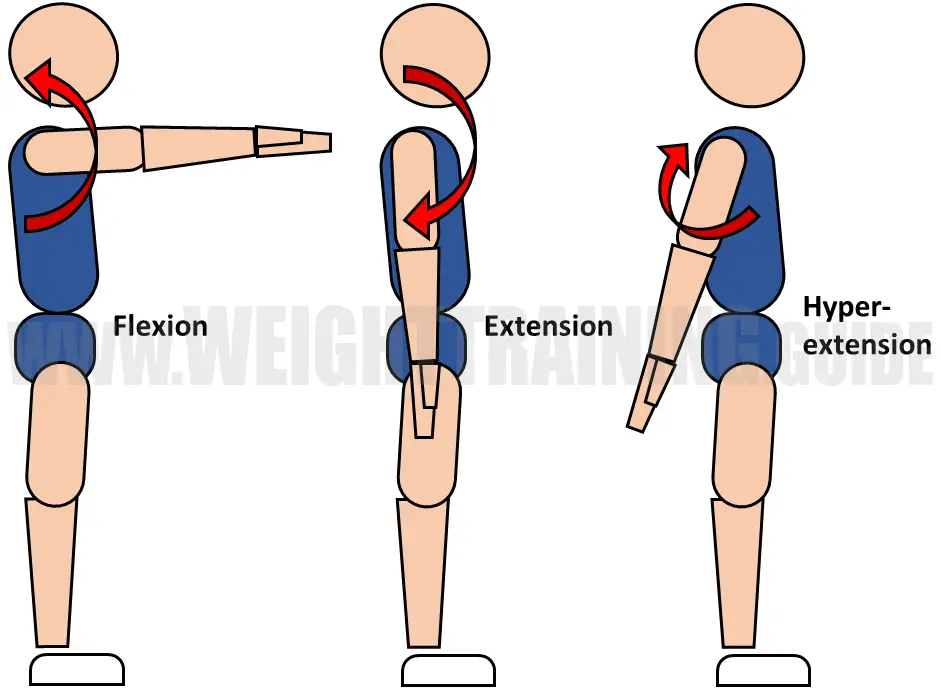

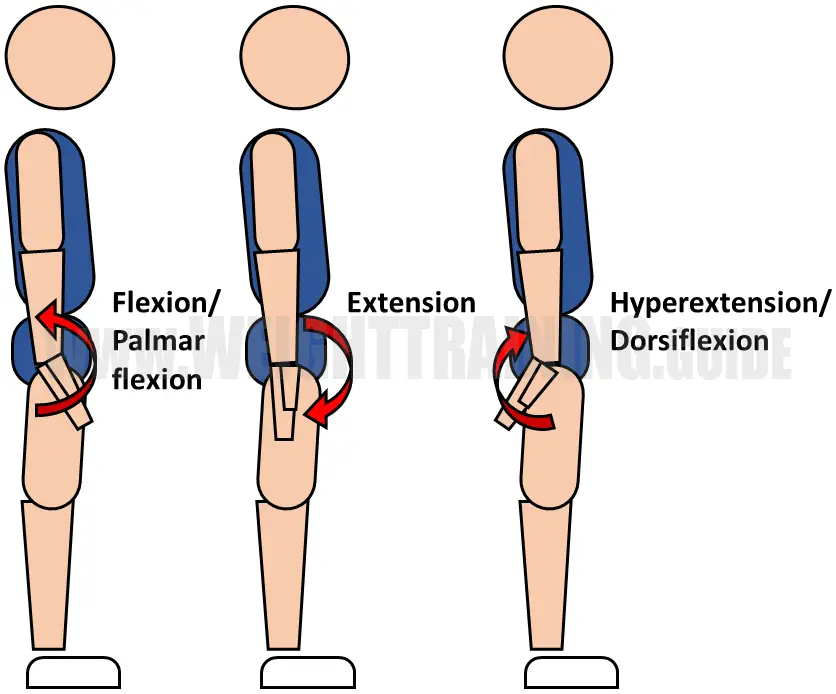

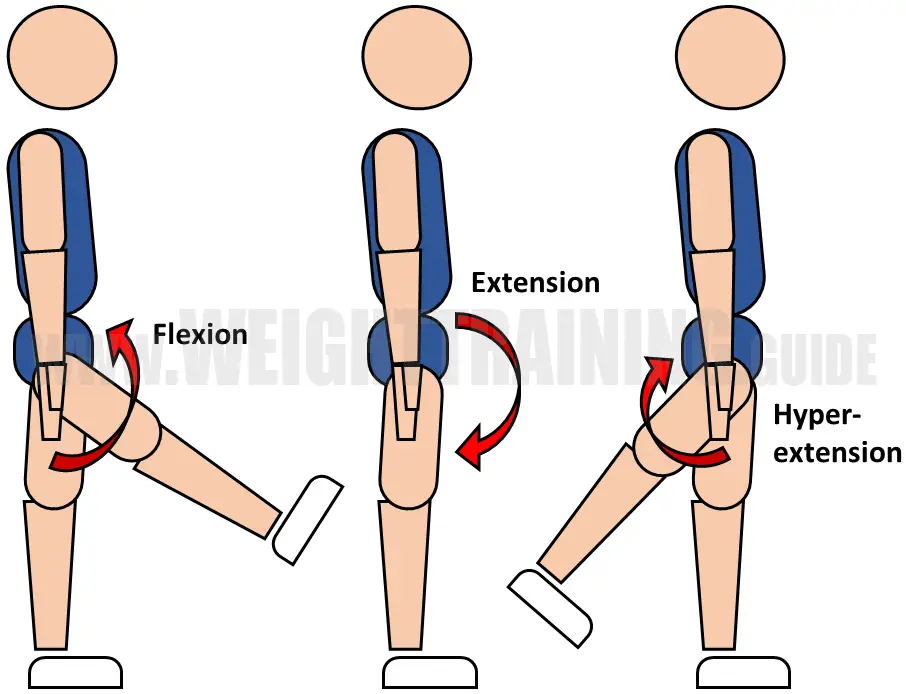

The sagittal plane divides your body into left and right halves. The joint articulations in this plane are flexion, extension, and hyperextension, which produce forward and backward movements.

- Flexion is an articulation of a joint in the sagittal plane that decreases the angle between the bones

- Extension is an articulation of a joint in the sagittal plane that increases the angle between the bones

- Hyperextension is not always possible. It is a continuation of extension passed the anatomical position, though still within the normal, healthy range of movement. (Note that, in medical terminology, ‘hyperextension’ often means to extend a joint beyond its normal, healthy range. On this website, I follow the definition that’s popular in sporting circles and in the strength and conditioning field)

Joints that you can flex and extend include your elbow and knee (figures 2 and 3, respectively).

Figure 2. Flexion and extension of the elbow.

Figure 3. Flexion and extension of the knee.

Joints that you can flex, extend, and hyperextend include your neck, waist, shoulder, wrist, hip, and ankle (figures 4 to 9).

Figure 4. Flexion, extension, and hyperextension of the neck.

Figure 5. Flexion, extension, and hyperextension of the waist.

Figure 6. Flexion, extension, and hyperextension of the shoulder.

Figure 7. Flexion, extension, and hyperextension of the wrist. When it comes to the wrist, flexion is often called ‘palmar flexion’, and hyperextension is often called ‘dorsiflexion’.

Figure 8. Flexion, extension, and hyperextension of the hip.

Figure 9. Flexion, extension, and hyperextension of the ankle. When it comes to the ankle, flexion is often called ‘plantar flexion’, and hyperextension is often called ‘dorsiflexion’.

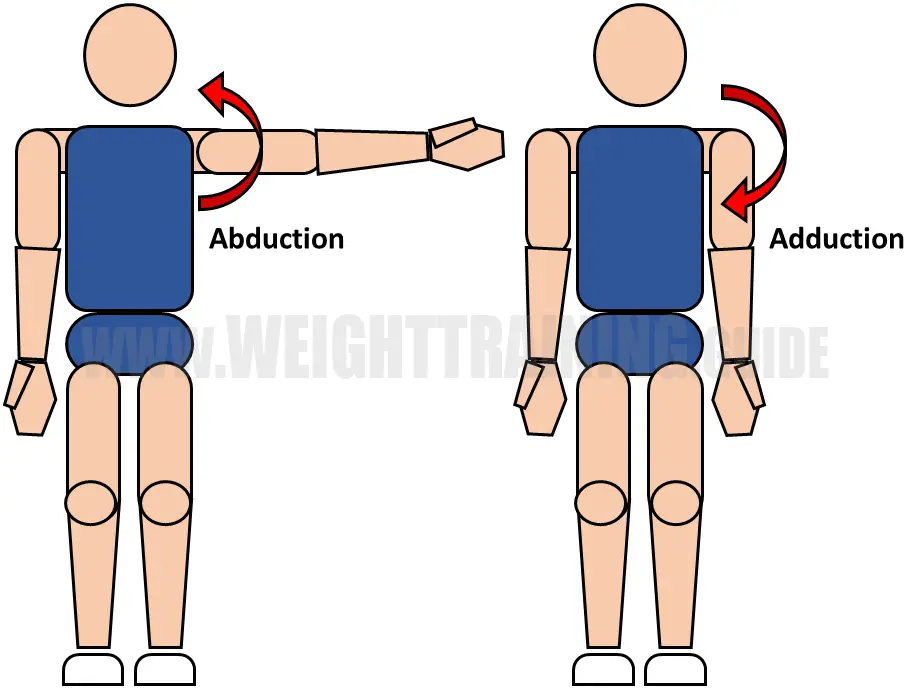

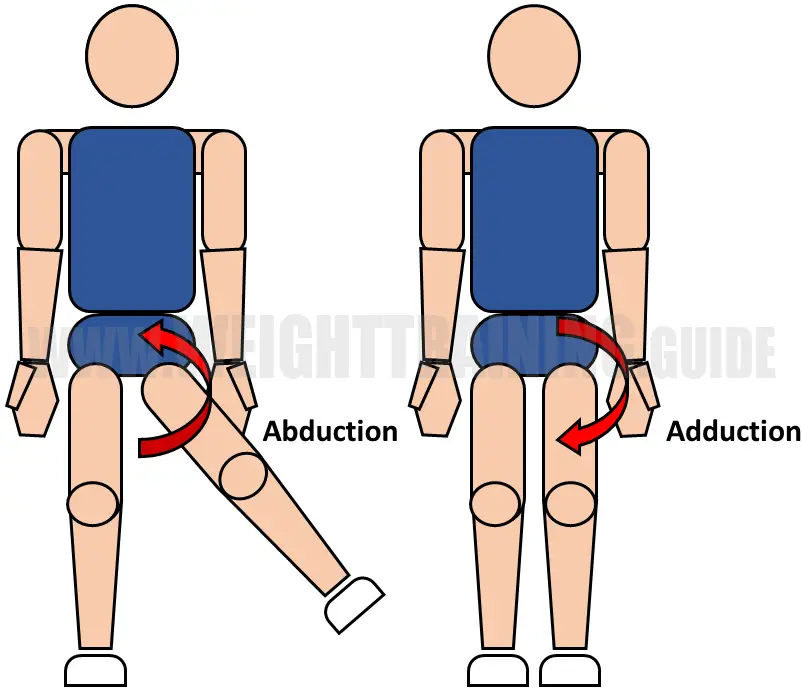

Joint articulations in the frontal plane

The frontal plane (also known as the coronal plane) divides your body into front and back halves. The joint articulations in this plane include abduction and adduction, which produce left and right movements.

- Abduction is an articulation of a joint away from the midline in the frontal plane

- Adduction is an articulation of a joint toward the midline in the frontal plane

Joints that you can abduct and adduct include your shoulder and hip (figures 10 and 11, respectively).

Figure 10. Abduction and adduction of the shoulder.

Figure 11. Abduction and adduction of the hip.

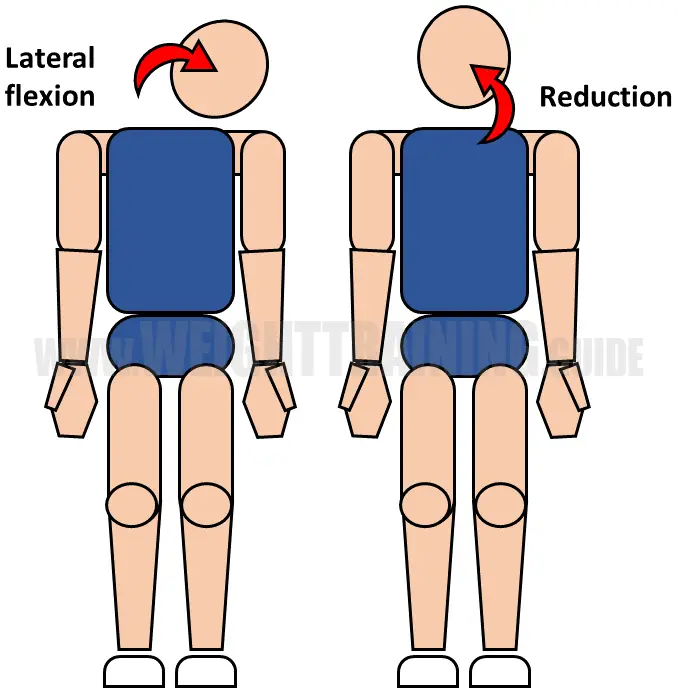

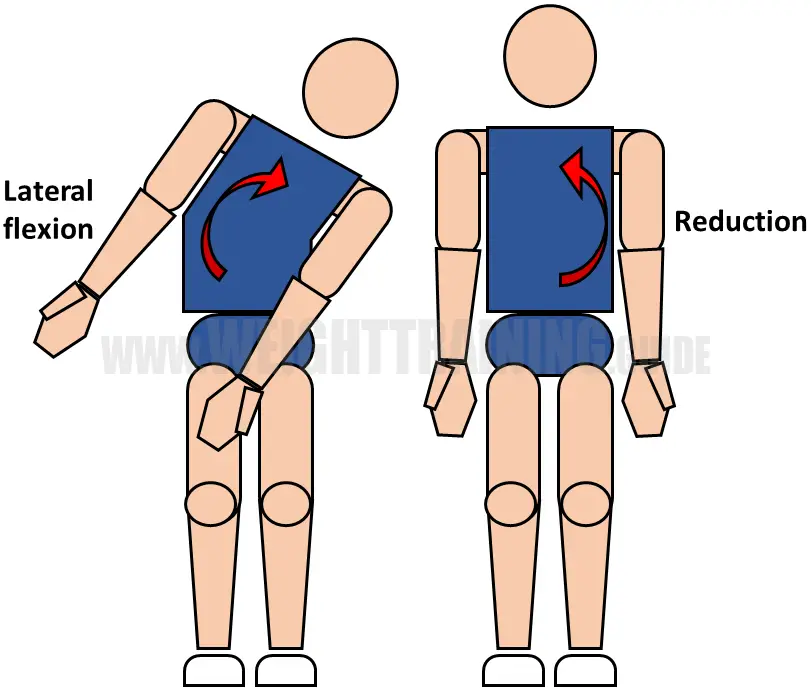

Other articulations in the frontal plane include lateral flexion and reduction, though these apply solely to your spine, particularly, your neck and waist (figures 12 and 13, respectively).

- Lateral flexion is an articulation of your neck or waist in the frontal plane away from the midline. The articulation can be either to the left or right

- Reduction is an articulation of your neck or waist in the frontal plane toward the midline

Figure 12. Lateral flexion and reduction of the neck.

Figure 13. Lateral flexion and reduction of the waist.

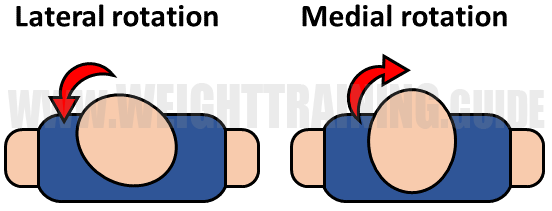

Joint articulations in the horizontal plane

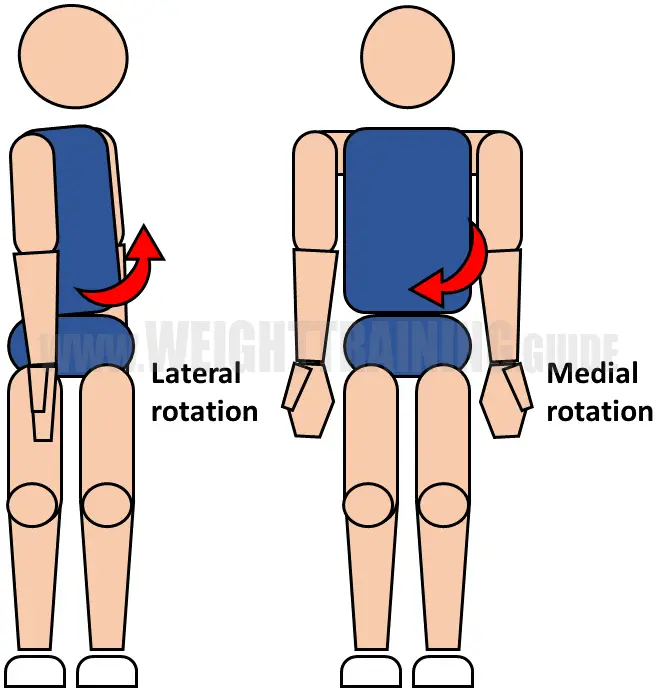

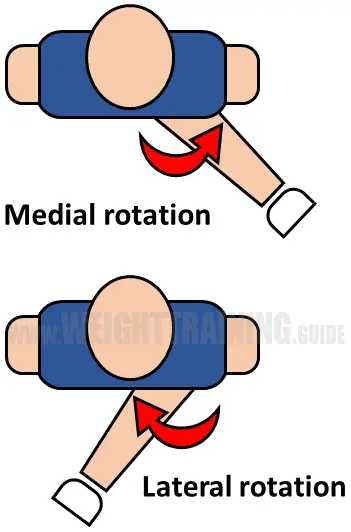

The horizontal plane (also known as the transverse plane) divides your body into upper and lower halves. The joint articulations in this plane include lateral rotation, medial rotation, supination, and pronation, all of which produce rotational movements.

- Lateral rotation (also known as external rotation) is rotation of a joint in the horizontal plane away from the midline

- Medial rotation (also known as internal rotation) is rotation of a joint in the horizontal plane toward the midline

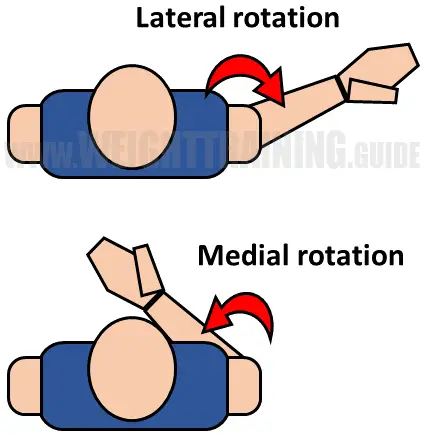

Joints that you can laterally and medially rotate include your neck, waist, shoulder, and hip (figures 14 to 17). Notice that, when it comes to your neck and waist, the lateral rotation can be to either the left or right, whereas when it comes to your shoulder and hip, the lateral rotation is restricted to one side.

Figure 14. Lateral and medial rotation of the neck. The lateral rotation can be to either the left or right.

Figure 15. Lateral and medial rotation of the waist. The lateral rotation can be to either the left or right.

Figure 16. Lateral and medial rotation of the shoulder. The lateral rotation is restricted to one side. In this figure, the elbow has been flexed to make the rotation of the shoulder clear.

Figure 17. Lateral and medial rotation of the hip. The lateral rotation is restricted to one side. In this figure, the knee has been flexed to make the rotation of the hip clear.

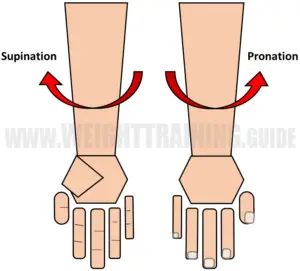

In weight training, pronation and supination mainly apply to the orientation of your forearm (Figure 18).

- Supination is to rotate your forearm so that your palm faces forward, as in the anatomical position

- Pronation is to rotate your forearm so that your palm faces backward

Figure 18. Supination and pronation of the forearm.

Note that a neutral forearm is one that has been rotated so that your palm faces the midsagittal line.

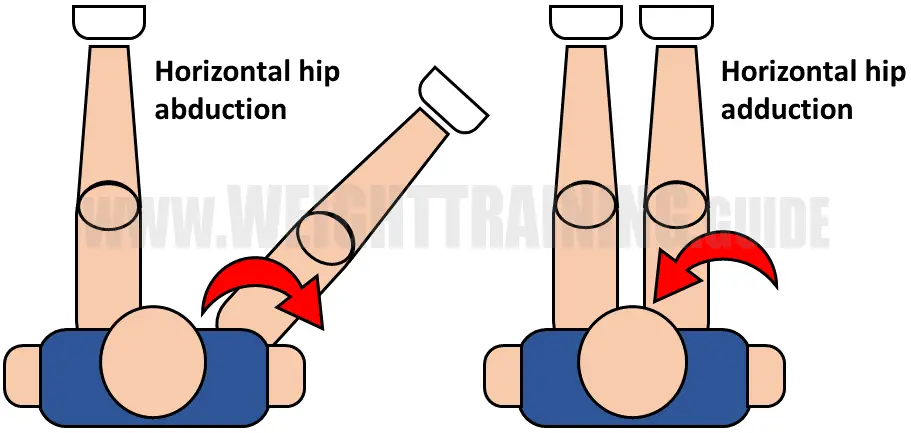

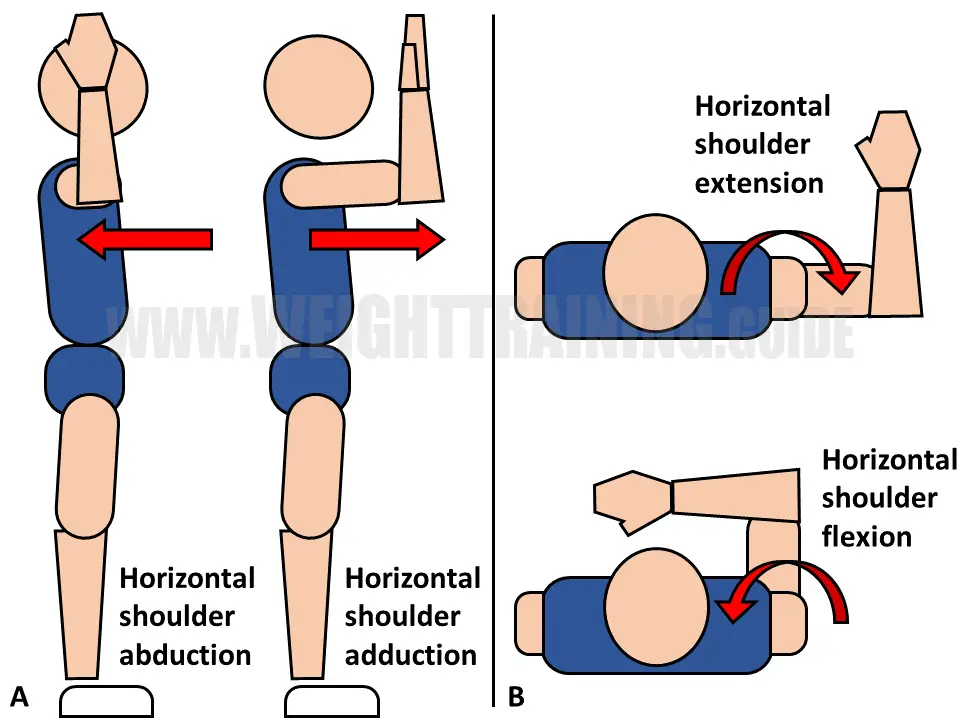

Other articulations in the horizontal plane include horizontal abduction, horizontal adduction, horizontal flexion, and horizontal extension, which apply only to your shoulder and hip. These movements do not start from the anatomical position; rather, they start from a position in which the shoulder/hip has been flexed so that the upper arm/thigh is perpendicular (at a right angle) to the torso.

You can perform two of the articulations—horizontal abduction and horizontal adduction—with your hip (Figure 19). Because your shoulder is much more mobile than your hip is, you can perform all four of the articulations with your shoulder (Figure 20, A and B).

- Horizontal hip abduction is an articulation of your hip away from the midline in the horizontal plane

- Horizontal hip adduction is an articulation of your hip toward the midline in the horizontal plane

Figure 19. Horizontal hip abduction and horizontal hip adduction.

- Horizontal shoulder abduction is an articulation of your shoulder away from the midline in the horizontal plane with your shoulder laterally rotated so that your elbow points downward

- Horizontal shoulder adduction is an articulation of your shoulder toward the midline in the horizontal plane with your shoulder laterally rotated so that your elbow points downward

- Horizontal shoulder extension is an articulation of your shoulder away from the midline in the horizontal plane with your shoulder medially rotated so that your elbow points out to the side

- Horizontal shoulder flexion is an articulation of your shoulder toward the midline in the horizontal plane with your shoulder medially rotated so that your elbow points out to the side

Figure 20. A. horizontal shoulder abduction and horizontal shoulder adduction; B. horizontal shoulder extension and horizontal shoulder flexion. To make the laterally/medially rotated shoulder clear, the elbow has been flexed in both A and B. Notice that in A, the elbow points downward, indicating that the shoulder is laterally rotated, whereas in B, the elbow points out to the side, indicating that the shoulder is medially rotated.

The role of muscles

All of the movements discussed above are, of course, made by muscles ‘pulling’ on the bones. Some muscles can only produce a single movement. For example, your brachialis, in your upper arm, can only flex your elbow. On the other hand, some muscles can contribute to a variety of movements. For example, your lower pectoralis major can extend, adduct, horizontally flex, horizontally adduct, and medially rotate your shoulder.

With everything above in mind, let’s now go over the main muscles that are activated by exercises that follow all major movement patterns, while avoiding as much mention of joint articulations and planes of motion as possible.